Within stifling dichotomies of normal and abnormal, lie millions of women, negotiating their identities. Accsex explores notions of beauty, the ‘ideal body’ and sexuality through four storytellers; four women who happen to be persons with disability. Through the lives of Natasha, Sonali, Kanti and Abha, this film brings to fore questions of acceptance, confidence and resistance to the normative. As it turns out, these questions are not too removed from everyday realities of several others, deemed ‘imperfect’ and ‘monstrous’ for not fitting in. Accsex traces the journey of the storytellers as they reclaim agency and the right to unapologetic confidence, sexual expression and happiness.

– Ghosh (2014)

A powerful line up makes for a powerful event, in more ways than one. To look again at the photograph, it’s far more than just a shot in time. It represents more than students, lecturers, activists, community members, allies, or otherwise interested people seeking alternative understandings of disability and gender coming together to connect (as if that isn’t exceptional enough). To me, the photograph is emblematic of the exciting possibilities that can emerge when the best parts of academia and activism come together. In this short post, I’d like to very briefly sketch out some points as to what this means to me as a disabled woman and scholar:

Safe(r) Spaces: Firstly, academic/activist events like this show that we can create (and demand) safe(r) spaces to speak about our lives as activists, campaigners, scholars and women. Events like this offer rare occasions for disabled women and their allies to come together, think together, politicise and rage together, and take solace in sharing intimate knowledges of our lives (that are seldom acknowledged or celebrated anywhere) together.

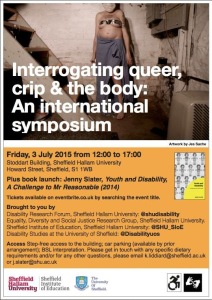

Resistance and intellectual freedom: In the context of the Academy, the fusion of academia and activism can offer refreshing spaces of resistance, creativity and (intellectual) freedom. Never has this been more important to counter the significant corporatisation and marketisation of higher education in the neoliberal University, and what some have called the privatisation of knowledge. Another recent event I helped organise, Theorising Dis/Ability, worked in similar ways. You can access the talks from the Theorising Dis/Ability seminar here. I’m currently co-organising another event with my friend Jenny Slater (Sheffield Hallam) around the intersections of queer and disability/crip activism, Interrogating queer, crip and the body: an international symposium, for which you can access free tickets here.

Making space for activist scholarship: For me personally/politically/professionally, academic/activist collaborations enable me to continue the work I love to do. It is a reminder of the importance of activist scholarship, which needs such spaces to not just survive, but thrive. I’m lucky that these loves are nurtured by many, many brilliant colleagues. For example, see the “dishuman” manifesto that I’m working on with exceptional folk like Katherine Runswick-Cole (MMU), Dan Goodley (University of Sheffield) and Rebecca Lawthom (MMU). This work is as theoretically rich as it is grounded in disabled people’s lives and meaningful social and political change.

The politics of visibility and disruption: Most importantly, academic/activist presences like those within the event above solicit/invite/welcome a multitude of bodies, minds, selves, knowledges and politics into the Academy. These are often bodies and selves that are at best tolerated, and at worst violated, in neoliberal educational spaces. To be present in the Academy in such ways – to proudly take up space, make noise, and be disruptive within the the very walls that so often exclude us – affirms Crip feminist power. Crucially, it does so in an academic landscape where we are largely absent as students, let alone as educators, speakers, creators, and leaders.

Note: This post is dedicated to the memory of Judith Snow who passed away on 31st May 2015. A proud disabled woman, visionary and advocate, she truly changed the world.